1901-1910: Federal government licensing of virus and toxin propagation establishments; criminalization of traffic in adulterated or misbranded drugs.

Part 3 of series on US federal quarantine and biological product law, 1798 to 1972

Orientation for new readers; American Domestic Bioterrorism Program; Tools for dismantling kill box anti-law

1798-1972 US federal quarantine and biological product law series:

1901 -1910: Federal government licensing of virus and toxin propagation establishments; criminalization of traffic in adulterated or misbranded drugs

By Lydia Hazel1 and Katherine Watt

Part 2 ended with:

1901 - Congress provided money and land to MHS Hygienic Laboratory for new building and for purchase of books and journals.

On March 3, 1901, through a funding act and a margin note — "Marine hospitals. Laboratory authorized." — Congress appropriated money and land for the Laboratory of Hygiene that had been in operation since 1887, originally in Staten Island NY, and had been relocated to Washington DC in 1891.

Congress gave the Marine-Hospital Service $35,000 and authorized transfer of five acres in Washington DC [Old Naval Observatory parcel] from the Navy to the Secretary of the Treasury, "for the erection of the necessary buildings and quarters for a laboratory for the investigation of infectious and contagious diseases, and matters pertaining to the public health, under the direction of the Supervising Surgeon-General."

Between 1900 and 1910, more biological products were propagated within and used in the United States, added to the smallpox and rabies vaccines and diphtheria and tetanus antitoxins already in use. The new additions included antibacterial antisera, thyroidectomized goat serum, and horse serum (1903 – 1907).

July 1, 1902 - Congress and President Theodore Roosevelt passed "An act to increase the efficiency and change the name of the US Marine-Hospital Service" - PL 57-236

In July 1902, Congress passed "An act to increase the efficiency and change the name of the US Marine-Hospital Service" to the Public Health and Marine-Hospital Service (PHMHS).

The 1902 reorganization and renaming law had nine sections.

At Section 1, Congress changed the name and transferred all the duties of the Marine-Hospital Service — "care of sick and disabled seamen and all other duties now required by law" — to the new PHMHS, still under the supervision of the Treasury Secretary.

At Section 2, Congress set the salary of the PHMHS Surgeon-General at $5,000 per year and dropped the modifier "supervising" from his title.

At Section 3, Congress authorized the Surgeon-General to "detail" commissioned PHMHS medical officers for duty in Washington DC to any of five PHMHS divisions, including marine hospitals and relief; domestic quarantine; foreign and insular quarantine; personnel and accounts; sanitary reports and statistics; and scientific research.

At Section 4, Congress authorized the President, "in his discretion, to utilize the PHMHS in times of threatened or actual war to such an extent and in such manner as shall in his judgment promote the public interest."

At Section 5, Congress established a nine-member advisory board for the Hygienic Laboratory that had been authorized a year before, to consult with the PHMHS Surgeon-General "relative to the investigations to be inaugurated, and the methods of conducting the same."

The advisory board would include three government officers appointed from the Army, Navy and Bureau of Animal Industry by, respectively, the Surgeon-Generals of the Army and Navy and the Secretary of Agriculture; the Hygienic Laboratory director (Milton J. Rosenau at the time); and five people "skilled in laboratory work in its relation to the public health, and not in the regular employment of the Government."

Section 6 authorized the PHMHS Surgeon-General, with the Treasury Secretary's approval, to appoint directors for three Hygienic Laboratory divisions: chemistry, zoology and pharmacology, and referred to the January 1889 law as governing the appointment of a director for the Hygienic Laboratory from among the commissioned medical officer corps.

Section 7 authorized the PHMHS Surgeon-General to organize conventions of state and territorial boards of health, quarantine boards and State health officers, and required him to organize at least one annual conference.

Section 8 directed the PHMHS Surgeon-General to establish a federal registry for "mortality, morbidity, and vital statistics" and create, distribute and collect forms for state health authorities to complete and return to the PHMHS for use in preparing national health reports, to "secure uniformity."

Section 9 authorized the President to prescribe rules and regulations for the conduct and internal administration of the PHMHS, and required the Treasury Secretary to file annual reports to Congress.

Main points to understand:

In 1902, Congress created a 9-member advisory board for the Hygienic Laboratory to provide input on "infectious and contagious diseases and matters pertaining to public health" (text from the March 1901 funding act authorizing the Hygienic Lab) "relative to investigations...and methods."

Congress did not assign biological product manufacturing regulation drafting or enforcement to the Hygienic Lab advisory board or to the Hygienic Lab employees.

Through the Virus-Toxin law, also passed July 1, 1902, outlined below, Congress assigned biological product manufacturing rule-making to a three-member board of Surgeon-Generals subordinate to the Treasury Secretary, and assigned enforcement to the Treasury Secretary and officers to whom he delegated authority.

In 1902, Congress set up a centralized data-collection system to collect information about births, deaths, diseases and causes of death.

This is important because the false attribution of disease and death to communicable pathogens is the primary means by which public health officers drive public fear of epidemics and pandemics, and thereby drive submission to products that the same government health officers falsely characterize as preventatives for so-called vaccine-preventable diseases.

By centralizing data collection, authorizing the Secretary of Treasury to create the forms to be used by state and local authorities, and funding publication and distribution of reports, Congress gave federal officers control over public perception of falsifiable and routinely-falsified communicable disease threats.

The centralization of information — enabling government control, coordination and falsification of disease and death evidence — began in 1902 with the law reorganizing and renaming the Marine-Hospital Service. Government control, coordination and falsification of disease and death data is currently carried out by government officers working at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), one of several federal offices whose functions originated in the Hygienic Lab.

July 1, 1902 - Congress and President Theodore Roosevelt passed "An act to regulate the sale of viruses, serums, toxins, and analogous products," the Virus-Toxin law, also known as Biologics Control Act - PL 57-244

On the same day that Congress reorganized the functions and changed the name of the Public Health and Marine-Hospital Service, Congress also passed "An act to regulate the sale of viruses, serums, toxins, and analogous products in the District of Columbia; to regulate interstate traffic in said articles, and for other purposes."

Congress passed the 1902 Virus-Toxin law ostensibly motivated by the deaths of 22 children in 1901 caused by tetanus-containing diphtheria antitoxin and smallpox vaccines: 13 children in St. Louis, MO who received diphtheria antitoxin, and nine in Camden, NJ who received smallpox vaccine. (Early smallpox vaccine manufacturing in the United States: Introduction of the “animal vaccine” in 1870, establishment of “vaccine farms” and the beginnings of the vaccine industry, Esparza et al, June 19, 2020, Vaccine).

The 1902 Virus-Toxin law had eight sections and went into effect six months from passage: Jan. 1, 1903. The law covered sale in the District of Columbia; interstate commerce in US-propagated products; export of US-made products to foreign countries; and import of foreign-made products into the United States.

Section 1 prohibited international and interstate sale, barter and exchange of "any virus, therapeutic serum, toxin, antitoxin, or analogous product applicable to the prevention and cure of diseases of man" unless the products had been "propagated and prepared at an establishment holding an unsuspended and unrevoked license, issued by the Secretary of the Treasury."

Section 1 required packages to be "plainly marked with the proper name of the article;" the name, address and license number of the manufacturer; and the "date beyond which the contents cannot be expected beyond reasonable doubt to yield their specific results."

Section 1 required the Treasury Secretary to notify the owner or custodian of a product if the establishment license had been suspended or revoked, and if no notice given, then sale, barter and exchange could continue, even without a license.

Section 2 prohibited falsification or alteration of package labels.

Section 3 provided that Treasury Department officers "may, during all reasonable hours enter and inspect any establishment."

Section 4 established a three-member board comprised of the Surgeon-Generals of the Army, Navy and Marine-Hospital Service, subject to Treasury Secretary approval, and conferred authority to the board "to promulgate from time to time such rules as may be necessary...to govern the issue, suspension and revocations of licenses." Section 4 also conditioned licensing of foreign establishments on the owners allowing the optional inspections authorized by Section 3.

Section 5 authorized and directed the Treasury Secretary to enforce the statute and any regulations issued by the Surgeon-Generals' board; authorized the Treasury Secretary to issue, suspend and revoke licenses; and authorized the Treasury Secretary to assign enforcement duties to other Treasury Department officers.

Section 6 prohibited interference with Treasury Department agents implementing the law.

Section 7 established as punishment for violations, fines not to exceed $500 or imprisonment up to one year.

Section 8 repealed all other Congressional acts inconsistent with the Virus-Toxin law provisions.

Key points to understand:

The 1902 Virus-Toxin law covered "any virus, therapeutic serum, toxin, antitoxin, or analogous product," but did not define any of those terms by measurable physical or chemical attributes.

The products were defined only by the clause: "applicable to the prevention and cure of diseases of man."

Vaccine was not listed as a product class subject to the 1902 Virus-Toxin law.

Congress didn't add the term vaccine to federal biological product law until 1970 (PL 91-515), 68 years after the Virus-Toxin law, 26 years after the 1944 Public Health Service Act, and 15 years after the nationwide, Congressionally-funded polio vaccination program began in 1955 (PL 84-377) with vaccines inflicted primarily on children and expectant mothers.

To date (2024), Congress and federal regulatory agencies have still not defined vaccine in measurable physical or chemical terms in any statute or regulation.

The 1902 Virus-Toxin law covered licensing of establishments only; it was silent on the licensing of individual products.

The 1902 Virus-Toxin law did not prohibit "manufacture" of viruses, toxins and other biological products without a license; it prohibited "sale, exchange and barter" of such products.

The 1902 Virus-Toxin law did not require labels to contain information about the identity, volume, concentration or purity of any substances or mixtures of substances in product packages.

The 1902 Virus-Toxin law did not set forth physical or chemical compliance standards for product identity, purity, or potency, or direct the Treasury Secretary or the three-member Surgeon-Generals board to establish or enforce compliance with physical or chemical standards.

The 1902 Virus-Toxin law did not define "specific results" and only required package labels to include the proper name of the article.

The 1902 Virus-Toxin law did not prohibit adulteration or misbranding of virus, toxin and serum package contents.

In contrast to the Pure Food and Drug Act passed in 1906 (summarized below), the 1902 Virus-Toxin law did not make reference to the US Pharmacopeia, which had been founded in 1820.

"...11 physicians came together to take action to protect patients from being harmed by the inconsistent and poor-quality medical preparations of the day. The first standards were "recipes" that guided the preparation of medicines, which were often made in apothecaries relying heavily on botanicals for their therapeutic benefit. As the practice of health and medicine evolved and the modern pharmaceutical industry emerged, USP standards changed from "recipes" to a set of quality specifications for medicines along with analytical tests to be performed to assess quality attributes."

The 1902 Virus-Toxin law did not authorize the three-member Surgeon-Generals board, or the PHMHS Surgeon-General, to enforce the laws, rules and regulations.

The 1902 Virus-Toxin law did not require inspections on any set schedule. It only established the optional right of Treasury Department officers to inspect establishments.

The 1902 Virus-Toxin law did not require manufacturers or sellers to submit specimens of products to federal laboratories for compliance testing; did not establish a federal laboratory responsible for testing of specimens; did not establish procedures for federal investigators to report non-compliant specimens to district attorneys for criminal prosecution of the manufacturers or sellers; and did not impose a duty of prosecution on district attorneys.

Most provisions of the 1902 Virus-Toxin law were incorporated into the 1944 Public Health Service Act (PHSA, PL 78-410) at Sections 351 and 352, codified currently at 42 USC 262, Regulation of biological products; 42 USC 262a, Enhanced control of dangerous biological agents and toxins; 42 USC 263, Preparation of biological products by [Public Health] Service; and 42 USC 263-1, Education on biological products.

June 30, 1906 - Congress and President Theodore Roosevelt passed "An act for preventing the manufacture, sale, or transportation of adulterated or misbranded or poisonous or deleterious foods, drugs, medicines, and liquors, and for regulating traffic therein," also called the Pure Food and Drug Act - PL 59-384

The Pure Food and Drug Act had 13 sections, and went into effect Jan. 1, 1907.

Section 1 prohibited "manufacture" of "any article of food or drug which is adulterated or misbranded" within any Territory or the District of Columbia. Manufacture within States was not mentioned. Violators would be guilty of misdemeanors, subject (for first violations) to fines up to $500, up to one year imprisonment or both.

Section 2 prohibited introduction of any adulterated or misbranded "article of food or drug" into any State, Territory or District of Columbia, from any other State, Territory or the District of Columbia, or to or from any foreign country. Violators who shipped, received, delivered, sold or offered for sale, exported or offered for export "adulterated or misbranded foods or drugs" would be guilty of misdemeanors, subject to fines of $200 to $300 and imprisonment up to one year, with an exemption for food or drugs "prepared or packed" in compliance with the laws of foreign countries, as long as the exempted food or drugs weren't sold or offered for sale domestically in the United States.

Section 3 directed the Treasury Secretary, Agriculture Secretary and Commerce and Labor Secretary to make rules and regulations, including rules governing "the collection and examination of specimens manufactured or offered for sale" in Territories, District of Columbia, States, or passing through ports, exempting food and drugs manufactured and used within one State (those that didn't cross State borders).

Section 4 directed that the Department of Agriculture Bureau of Chemistry would carry out the "examinations of specimens," or at least direct and supervise examinations, to find out if the articles of food and drugs were adulterated or misbranded. Congress directed the Agriculture Secretary to notify the manufacturer if examiners found adulterated or misbranded specimens, and to set rules through which manufacturers could be heard if they wanted to challenge the findings. If, after a hearing, the Agriculture Secretary still believed the articles were adulterated or misbranded, Congress directed him to "certify the facts to the proper US district attorney with a copy of the results of the analysis or the examination...authenticated by the analyst or officer" under oath. Congress directed the regulators (Treasury, Agriculture and Commerce-Labor secretaries) to prescribe rules for the public to be notified of any ensuing court judgment.

Section 5 established the duty of the district attorneys to prosecute violators "in the proper courts...without delay" upon presentation of the certified evidence, to enforce the criminal penalties outlined in Sections 1 and 2.

Section 6 defined the term "drug" as "all medicines and preparations recognized in the United States Pharmacopeia-National Formulary [USP-NF] for internal or external use, and any substance or mixture of substances intended to be used for the cure, mitigation, or prevention of disease of either man or other animals."

Congress defined "food" as "all articles used for food, drink, confectionery, or condiment by man or other animals, whether simple, mixed, or compound."

Section 7 defined the term "adulterated." For drugs sold under USP-NF names and monographs, a drug would be deemed adulterated under either of two conditions.

A drug would be deemed adulterated if it "differs from the standard of strength, quality, or purity, as determined by the test laid down" in the USP-NF "official at the time of investigation" but provided that drugs listed by name in the USP-NF would not be deemed adulterated as long as the "standard of strength, quality or purity" was "plainly stated on the bottle, box, or other container" even if the standard differed from the standard determined by the USP-NF test.

A drug would also be deemed adulterated if the product's "strength or purity fall below the professed standard or quality" stated on the package under which it was sold.

Section 7 also defined the term "adulterated" for confectionery and food, but those definitions are not summarized here.

Section 8 defined "misbranded" as applying to all drugs, articles of food, or "articles which enter into the composition of food" enclosed in packages with any statements about the article, ingredients or substances that were "false or misleading in any particular," including false statements about the State, Territory or country in which the article was produced.

Section 8 further defined "misbranded" drugs as those that were "an imitation of or offered for sale under the name of another article" and drugs in packages that had had original contents removed and substituted with other contents, or if the package label failed to list the "quantity or proportion of any alcohol, morphine, opium, cocaine, heroin, alpha or beta eucaine, chloroform, cannabis indica, chloral hydrate, or acetanilide, or any derivative or preparation of any such substances."

Section 8 also defined "misbranded" food, and listed exemptions from misbranding, but those definitions and exemptions are not summarized here.

Section 9 provided that "dealers" of food and drug articles could be exempt from prosecution if they had obtained a "guaranty signed by the wholesaler, jobber, manufacturer" or other supplier of the products, asserting that the products were not adulterated or misbranded, as long as the guaranty listed the name and address of the supplier and made clear that the supplier would bear legal responsibility if specimen testing found evidence of adulteration or misbranding.

Section 10 provided "libel for condemnation" procedures, not summarized here.

Section 11 directed the Treasury Secretary to collect and supply "samples of food and drugs" being imported into the US and to provide notice to the owner of such imported products to appear before the Agriculture Secretary and introduce testimony. Section 11 provided for the Treasury Secretary to forbid entry to products found to be adulterated or misbranded, with exceptions covering "penal bonds."

Section 12 defined "Territory" as including the insular possessions of the United States, and "person" as singular and plural, including corporations, companies, societies and associations.

Section 13 set Jan. 1, 1907 as the date of effect.

Key points:

The 1906 Pure Food and Drug Act indicates that Congress members understood the public dangers posed by adulterated and misbranded pharmaceutical products. They were capable of establishing definitions for terms including drug, adulteration and misbranding. They were capable of assigning responsibility for establishing physical and chemical standards, assays and testing methods to a non-governmental organization (US Pharmacopeia-National Formulary). They were able to establish procedures for collecting and testing specimens and able to designate federal government agencies and officers to collect and test specimens, and testify under oath as to their adulterated or misbranded status. They were able to set up procedures for district attorneys to prosecute violators who manufactured adulterated and misbranded products.

Domestic and foreign manufacturing and foreign and interstate traffic in "virus, therapeutic serum, toxin, antitoxin, or analogous product" were not governed by the 1906 Pure Food and Drug Act.

Viruses, serums, toxins, antitoxins and analogous products were governed by the 1902 Virus-Toxin law, and therefore not subject to physical and chemical standards, specimen collection, specimen testing or criminal prosecution for adulteration or misbranding.

Most provisions of the 1906 Pure Food and Drug Act were incorporated into the 1938 Food Drug and Cosmetics Act (FDCA, PL 75-717), and are currently codified at several sections in Title 21, Chapter 9, Section 301 et seq.

Congressional funding

As laid out in Part 2 of this series, during the 19th century, funding for the Marine-Hospital Service came from taxes levied first on seamen as wage taxes, and then on cargo, through tonnage taxes levied on ship owners.

The tonnage tax financing system was repealed in 1905, when Congress began making regular appropriations to the institution that was, by that time, called the Public Health and Marine-Hospital Service. (1904-1943 Congressional funding acts, compilation, at p. 6 of 121 pp. PDF)

In 1878, Congress passed the first federal quarantine law covering quarantine of passengers, crew and goods on ships arriving in US ports from foreign ports.

In 1890, Congress authorized the Marine-Hospital Service to take charge of interstate quarantine — control of people and goods attempting to cross state borders. Congress expanded MHS quarantine powers in 1893.

Between 1904 and 1910, Congress made annual appropriations to the Public Health and Marine-Hospital Service, under Treasury Department appropriations, for several divisions and programs: Office of the Surgeon-General, including medical examinations and treatment at marine hospitals; Quarantine Service; Prevention of Epidemics; printing costs for publishing communicable disease reports (about $500 per year), and money for purchasing books and journals (also about $500 per year)

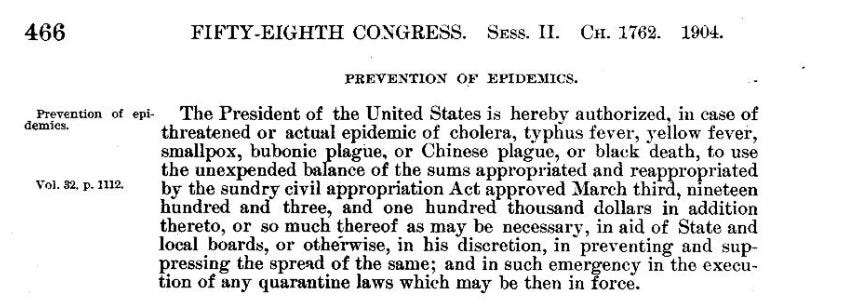

Through the Prevention of Epidemics section, Congress authorized and funded the President to provide money "in aid of State and local boards [of health]" in case of "threatened or actual epidemics" of named diseases.

The Prevention of Epidemics program was the forerunner of what became known as the Federal-State Cooperation program in the 1944 Public Health Service Act (PHSA Part B, Section 311 et seq, 56 Stat 693, currently codified at 42 USC 243 et seq., including "public health emergencies" provisions added in 1983 (PL 98-48), repealed and replaced in 2000 (PL 106-505); the "targeted liability protections for pandemic and epidemic products and security countermeasures" (liability exemptions) added in 2005 through the PREP Act (PL 109-148), and many related provisions.

In 1904, Congress appropriated $335,000 for Quarantine Service and $100,000 for Prevention of Epidemics.

In 1905, Congress repealed the cargo tonnage tax source of PHMHS funding and directly appropriated $200,000 for the Public Health and Marine-Hospital Service, along with $340,000 for Quarantine Service and $100,000 for Prevention of Epidemics.

In 1906, Congress gave Treasury $1,185,000 for the PHMHS, including pay and quarters for officers, pay for all other staff, hospital maintenance costs, medical examination and treatment costs, books and journals, and a line item for the Hygienic Laboratory of $15,000. Congress also gave the Treasury Department $340,000 for Quarantine Service and $200,000 for Prevention of Epidemics.

In 1907, Treasury received $1,162,750 for PHMHS, including $15,000 for the Hygienic Lab; $350,000 for Quarantine Service; $200,000 for Prevention of Epidemics.

In 1908, Treasury received $1,299,750 for PHMHS, including $15,000 for Hygienic Lab maintenance and $10,000 to equip a new Hygienic Lab building; $400,000 for Quarantine Service; and $500,000 for Prevention of Epidemics.

In 1910, Treasury received $1,156,100 for PHMHS, including $15,000 for the Hygienic Lab; $400,000 for Quarantine Service, and authorization for the President to use "unexpended balance of sums...approved March 4, 1909" for Prevention of Epidemics, to fund state and local health board projects to prevent alleged epidemics.

1910 JAMA papers by Milton Rosenau, Director of PHMHS Hygienic Laboratory

In 1910, seven years after the Virus-Toxin law went into effect on Jan. 1, 1903, Milton Rosenau, the second director of the Hygienic Laboratory (1899-1909), published two papers in the Journal of the American Medical Association: The Federal Control of Serums, Vaccines, Etc. and Vaccine Virus.

In the first paper, Rosenau described an inspection and licensing program that he claimed was operated by the staff of the Hygienic Laboratory division of pathology and bacteriology, including purchase of samples from manufacturing establishments and "on the open market" for "examination as to potency and purity."

Rosenau further claimed that the licensing process applied to individual products and that "general licenses authorizing the manufacture of any and all biologic products are not issued," even though the 1902 law only addressed the licensing of establishments and did not define or authorize the Treasury department to adopt or enforce product standards.

After describing inspectors inquiring into "methods of manufacture," the "competency" of employees and the "efficiency of the material equipment," Rosenau concluded: "At present every confidence may be had in all biologic products made under government license."

The last section of Rosenau's paper on federal control is titled "Government Guarantee" and states:

"The government does not guarantee that each vaccine point or each package of antitoxin will produce its full therapeutic effect and be free from all danger. This would be impracticable with the extent and variety of the business in biologic products now carried on in this country and abroad..."

In the second paper, Rosenau described vaccine virus as "the specific principle in the material obtained from the skin eruption of calves having a disease known as vaccinia [cowpox]…" and stated "both the pulp and the lymph are mixtures containing epithelial cells, serum, blood, leucocytes, products of inflammation, debris, bacteria, etc., in varying proportions."

Rosenau admitted "the specific principle of vaccinia [cowpox] is unknown;" stated that "it is impossible to obtain vaccine virus free from the bacteria of the skin;" and stated "the fact that a serum or vaccine is granted a license does not mean that it is a valuable curative or prophylactic; in fact, it may have little or no therapeutic value."

He stated: "it is evidently the province of the medical profession to determine for itself whether a certain substance has therapeutic value or not. The chief concern of the government is to protect the practitioner against sophistications, impurities, faults or mislabeling."

Rosenau did not point out to JAMA readers that the 1902 Virus-Toxin law was silent on identity, purity and labeling of products by physical and chemical composition and ingredients; the 1902 law did not prohibit adulteration and misbranding; and the 1902 law did not establish prosecutorial procedures.

Rosenau ended his paper with an argument for adding vaccine virus to the US Pharmacopeia, from which it is possible to infer that US Pharmacopeia officials were resisting such efforts:

The objection, that vaccine virus is an indefinite substance, the ‘active principle’ of which is not known, is no longer valid, for the Pharmacopeia contains many such substances, including the ferments, against which similar objection holds.

The objection that vaccine virus cannot be “assayed” [quantitatively and qualitatively analyzed to determine the presence, amount or functional activity of a substance] by the average druggist also lacks force when we recall that the potency and purity of vaccine virus in interstate traffic is cared for by the federal government under the law of July 1, 1902, which relieves the pharmacist of this responsibility…

Again: the words potency, purity and vaccine do not appear in the July 1902 Virus-Toxin law, nor do the words adulteration or misbranding.

These papers confirm that Rosenau understood that vaccine virus was "an indefinite substance" that could not be identified, purified or subjected to any measurable standards for product identity, purity or potency; that no such standards had been established by federal officers or by the US Pharmacopeia acting as a private-sector product quality monitor in partnership with government agencies; that no tests had been developed or were being used by Hygienic Lab workers to test vaccine virus specimens for compliance with non-existent identity, purity and potency standards; and that no criminal prosecution of propagation, sale and use of adulterated or misbranded vaccine virus was authorized or carried out.

The real purpose of the 1902 Virus-Toxin law was to create initial false public confidence in vaccines.

One of several real purposes for the Hygienic Laboratory and two of its successor organizations today (NIH and FDA) was to serve as front organizations that have never and still do not establish physical or chemical standards, or safety or efficacy standards, for vaccines; have never and still do not conduct product testing to verify manufacturer and public health officer claims as to product identity, purity, potency, safety or efficacy; and have never and still do not support criminal prosecution for manufacture, distribution and use of vaccines and related products.

The Hygienic Lab, NIH and FDA have merely pretended to regulate biological products, to falsely generate and maintain public confidence in vaccines, which were then and are still today, demonstrably heterogeneous, unstable and toxic products.

Since 1902, the biological product regulatory acts that public officials have lied about conducting, they could not and did not conduct in reality.

In the early days, they failed to establish and enforce physical and chemical standards because they lacked the necessary scientific knowledge, methods and equipment, although they demonstrably knew, from anaphylaxis studies, that foreign cells and cell products, especially proteins, when injected into the bloodstream, are inherently harmful to recipients.

In more recent decades, purported regulators did not and do not establish and enforce physical and chemical standards because scientific knowledge, methods and equipment have developed to the point where the results of any tests would disclose the inherent heterogeneity, instability and toxicity of products they need to deceive the public into believing to be pure, stable and beneficial.

Related:

July 11, 2024 - On "unavoidable, adverse side effects" as deceptive language used to conceal the intentionality of vaccine toxicity

Aug. 26, 2024 - Intentional elusivity of definitions for virus and vaccine.

Aug. 28, 2024 - On 'critical quality attributes' or CQAs

Lydia Hazel holds degrees in Latin (BA) and linguistics (MA), with minors and concentrations in mathematics, phonetics/phonology, and philology. Her professional background is teaching English as a Second Language. She raised four children, unvaccinated since 1993, after Hazel investigated vaccines when Hepatitis B vaccines were added to the CDC-recommended childhood immunization schedule. She lives in Illinois and is the author of the Medical Countermeasures Awareness Act posted at Bailiwick in February 2024. Email: lydiahazel@aol.com.