Note: My dog was running around during the last 10 minutes of the recording, eating out of his bowl, jingling his tags and clacking his toenails on the floor. So those sounds are in the background. Readers who find background sounds annoying shouldn’t listen to this recording. I’ll do better next time.

Documents:

July 1968 - Pope Paul VI, Humanae Vitae

June 1978 - Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn, A World Split Apart

July 1978 - Malcolm Muggeridge, On Humanae Vitae

Transcript, edited:

I'm going to read a transcript of a speech given by Malcolm Muggeridge in July of 1978 in San Francisco, and it is a speech about the 10th anniversary of the papal encyclical called Humanae Vitae, which was issued by Pope Paul VI on July 25th, 1968.

Malcolm Muggeridge was a British writer. He wrote about social and political issues. He was born in 1903 and he died in 1990. For most of his life, he was an agnostic, but he converted to Christianity in the late 1960s and then converted to Catholicism in 1982 at the age of 79. This speech was given when he was a Christian, but not yet a Catholic.

I'm reading it because, there are several writers who I read a lot, to try to understand the historical arc that led to where things are now and the difficulties that humanity is dealing with now, because those things, the things that we're dealing with now, have predicates.

They have things that happened in the past that have made what's happening now, not only possible, but kind-of essential. They couldn't have gone a different way once those past things had happened.

Some of those writers, if readers are interested in looking into their work yourselves, are

Pope Leo XIII

G.K. Chesterton

Fulton J. Sheen

C.S. Lewis

Josef Pieper

Christopher Dawson

Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn

Archbishop Marcel Lefebvre

Walker Percy

Malachi Martin

I'm just going to read the speech and maybe talk a little bit about it after I get done doing that.

Malcolm Muggeridge, On Humanae Vitae.

I find myself in a way in a curious position. After all, I'm not a Catholic. I haven't that great satisfaction that presumably most of you have. At the same time, I have a great love for the Catholic Church and I've had from the beginning of feeling stronger than I can convey to you that this document, Humanae Vitae, which has been so savagely criticized sometimes by members of your church, is of tremendous and fundamental importance and that it will stand in history as tremendously important. And that I would like to be able to express, and I'm happy to have occasion this evening to express, this profound admiration that I have for it. This profound sense that it touches upon an issue of the most fundamental importance and that it will be, in history, something that will be pointed to both for its dignity and for its perspicuity.

[So Humanae Vitae is a papal encyclical about birth control. And papal encyclicals, I think most Vatican documents, are named after the first few Latin words of their Latin version, and it's on human life, the transmission of human life. Back to the speech.]

It happens 10 years ago that I found myself in the position of introducing a discussion on Humanae Vitae in a BBC television program on a Sunday evening. And I can remember it very vividly. The people who are assembled for these discussions or panels on the BBC fall usually into various categories, which are invariable. You generally have a sociologist from Leeds. You also have a life purist, usually with a mustache. You also have a knockabout clergyman of no particular denomination and enormous mutton chop whiskers. And you have, I regret to say also, usually a rather dubious father, which we had on this occasion, when I really very much wanted to have someone who was a passionate supporter of Humana Vitae.

However, I did have someone whom you're going to be fortunate enough to hear in the course of this symposium. And that was Dr. Colin Clark, who has so marvelously and effectively dealt with what I consider to be one of the great con tricks in this whole controversy of contraception and related matters, the population explosion. So he was a great solace and comfort.

And then in the course of presenting the program, something happened, which gave me inconceivable delight, and which was also in its way extremely funny, because I often think that the mercy and wisdom of God comes to us more in humorous episodes than in solemn ones. In this program, the various people spoke for the first time, as the various people spoke for the first time, a short description of them was appended. And there had been prepared to append to Dr. Colin Clark's appearance, "Father of eight." But by a happy chance, this description got shifted to the "dubious father," so that he appeared on the program as a father of eight. You must agree with me that somewhere or other there is the hand of a loving God who also has, as an all-loving God must necessarily have to look after a human race such as ours, a tremendous sense of humor. Anyway, that was that.

Now tonight, I find myself 10 years later in the position of being responsible for what is called the keynote address. And after thinking about it and scribbling down a few notes (that I'm glad to say I haven't brought with me), I wondered what sort of a keynote address I could hope to present to a gathering, most of whose members would certainly know far more about the matter under discussion than I do, and be far better versed in assembling the pros and cons of it.

And then a rather interesting and indeed uplifting thought struck me that, of course, I couldn't hope to deliver a keynote address on this particular subject because the keynote address had already been delivered 2000 years ago.

In other words, this matter, which, as I've said, is of such tremendous importance, is an integral part of the revelation that came into the world in the Holy Land. That stupendous drama which has played such a fantastic role in the story of 2,000 years of Christendom: the birth, the life, the ministry, the death and the resurrection of Jesus Christ as recounted in the Gospels. That was the keynote address for the matter before us this evening.

And after all that keynote address, having been given to the world in those marvelous words of the fourth gospel, that the word that became flesh and dwelt among us, full of grace and truth, that Word, that keynote address for all the centuries of our Western civilization, was itself carried by the Apostle Paul to a Roman world, which was as bored, as derelict, as spent, as our civilization often seems today. Carried to it to animate it, to bring back the creativity which had been lost, to fill the world with great expressions in music, in architecture, in literature, in every sort of way of this great new revelation.

Now, why do I think that this was veritably our keynote address? Because in that revelation, an integral part of that revelation — also something that was wonderfully novel and fresh to a tired and jaded world — was the sacramental notion. So that out of, for instance, the simple need of men to eat and drink came the blessed sacraments. And similarly, out of the creativity in men, their animal creativity, came the sacrament of love; the sacrament of love, which created the Christian notion of family, of the marriage, which would last, which would be something stable and wonderful in our society, out of which it came. And which has endured through all those centuries until now, when we find it under attack.

In my opinion, what has brought about in the first case, this great weakening of the marvelous sacrament of reproduction, has been precisely what Humanae Vitae attacks and disallows. The procedures whereby eroticism, by its condition which is lasting love, becomes relegated to be a mere excitement in itself. And thereby are undermined not just relations between this man and that woman, but the whole shape and beauty and profundity of our Christian life.

Humanae Vitae recognized this and asked of Catholics what many of them were unable to accord, that they should not fall into this error, that they should eschew this dangerous procedure, which was now being made available in terms at once infinitely simple, but also infinitely more dangerous, namely the birth pill.

Now whether and how far and to what extent this inhibition is or can be or will be acceptable, it's not for me to say. What I want to say tonight as a non-Catholic, as an aspiring Christian, as someone who as an old journalist has watched this process of deterioration in our whole way of life, what I want to say is that in that encyclical, the finger is pointed on the point that really matters. Namely, that through human procreation, the great creativity of men and women comes into play. And that to interfere with this creativity, to seek to relate it merely to pleasure, is to go back into pre-Christian times and ultimately to destroy the civilization that Christianity has brought about.

That is what I want to testify to as just one individual who has been given the great honor of coming and starting off your discussions. If there is one thing I feel absolutely certain about, it is that. One thing that I know will appear in social histories in the future is that the dissolution of our way of life, our Christian way of life, and all that it has meant to the world, relates directly to the matter that is raised in Humanae Vitae.

The journalists, the media, write and hold forth about the various elements in the crisis of the Western world today. About inflation, about overpopulation, about pending energy shortages, about detente, about hundreds of things. But they overlook what your church has not overlooked, this basic cause: the distortion and abuse of what should be the essential creativity of men and women, enriching their lives as it has and does enrich people's lives.

And when they are as old as I am, enriches them particularly beautifully when they see, as they depart from this world, their grandchildren beginning the process of living which they are ending. There is no beauty, there is no joy, there is no compensation that anything could offer in the way of leisure, of so-called freedom from domestic duties, which could possibly compensate for one thousandth part of the joy that an old man feels when he sees this beautiful thing: life beginning again as his ends, in those children that have come into the world through his love and through a marriage which has lasted through 50 and more years.

I assure you that what I say to you is true and that when you are that age, there is nothing this world can offer in the way of success, in the way of adventure, in the way of honors, in the way of variety, in the way of so-called freedom, which could come within a hundredth part of measuring up to that wonderful sense of having been used as an instrument, not in the achievement of some stupid kind of personal erotic excitement, but in the realization of this wonderful thing, human procreation.

Now, of course, when Humanae Vitae was published to the world and was set upon by all the pundits of the media, it was attacked as being a failure to sympathize with the difficulties of young people getting married. That was the basis on which the attack was mounted. But it was perfectly obvious, and Colin Clark will remember from that symposium with which the coming of Humanae Vitae was celebrated by the BBC -- it was mentioned then that contraception was something that would not just stop with limiting families, that in fact it would lead inevitably as night follows day to abortion and then to euthanasia. And I remember that the panel jeered when I said particularly the last, euthanasia.

But it was quite obvious that this would be so. That if you once accepted the idea that erotic satisfaction was itself a justification, then you had to accept also the idea that if erotic satisfaction led to pregnancy, then the person concerned was entitled to have the pregnancy stopped. And of course, we had these abortion bills that proliferated through the whole Western world. In England, we have already destroyed more babies than lives were lost in the First World War. Through virtually the whole Western world, there now exists abortion on demand. The result has been an enormous increase in the misery and unhappiness of individual human beings, and again, the enormous weakening of this Christian family.

I should mention to you that the point has been reached in England where a bishop has actually produced a special prayer to be used on the occasion of an abortion. You know, one of the great difficulties in being editor of Punch was something that I hadn't envisaged when I took the job on. And that is that whenever you tried to be funny about somebody, you would invariably find that something they actually did was funnier than anything that you could possibly think of. I really don't know how you could get a better example of it than a bishop solemnly setting to work to produce a measured prayer on the occasion of murdering a baby. But that is actually what has happened.

Now we move on to the next stage in this dreadful story. And it's all this that is implicit in the encyclical we're talking about. If it is the case that the only consideration that arises is the physical well-being of individual people, then what conceivable justification is there for maintaining at great expense and difficulty the people who are mentally handicapped, the senile old? I myself have long ago moved into what I call the NTBR belt. And the reason I call it that is because I read about how a journalist who had managed to make his way into a hospital ward had found that all the patients in the ward who were over 65 had N-T-B-R on their medical cards. And when he pressed them to tell him what these initials stood for, he was told, "Not to be resuscitated."

Well, I've been in that belt for some ten years, so I know that as sure as I can possibly persuade you to believe, this is what is going to happen. Governments will find it impossible to resist the temptation with the increasing practice of euthanasia, though it is not yet officially legal, except in certain circumstances, I believe, for instance, in this state of California. The temptation will be to deliver themselves from this burden of looking after the sick and imbecile people or senile people by the simple expedient of killing them off.

Now this is in fact what the Nazis did. And they did it not, as is commonly suggested, through slaughter camps and things like that, but by a perfectly coherent decree with perfectly clear conditions. And in fact it is true that the delay in creating public pressure for euthanasia has been due to the fact that it was one of the war crimes cited at Nuremberg. So for the Guinness Book of Records, you can submit this, that it takes just about 30 years in our humane society to transform a war crime into an act of compassion. That is exactly what happened.

[Because the Nuremberg trials were in the late 1940s. And again, he's giving this lecture in 1978 in California.]

So you see the thought, the prayer, the awareness of reality behind Humanae Vitae has, alas,

been amply borne out precisely by these things that have been happening. I feel that Western man has come to a sort of parting of the ways, and that as time goes on, you who are much younger will realize this, in which these two ways of looking at our human society will be side by side, and it will be necessary to choose one or the other.

On the one hand, the view of mankind, which has all through the centuries of Christendom been accepted in one form or another by Western people, that we are a family, that mankind is a family with God, who is the Father. In a family, you don't throw out the specimens that are not up to scratch. In a family, you recognize that some will be intelligent and some will be stupid. Some will be beautiful and some will be ugly. But what unites the family is the fatherhood of God.

Now what our way of life is now moving towards is the replacement of this image of the family by the image of a factory farm in which what matters is the economic prosperity of the family and of the livestock so that all other considerations cease to be relevant. And you will find that this terrible notion increasingly occupies the minds of people and becomes acceptable to them.

There is something else that is envisaged in the encyclical that we are talking about. I wanted to say to you how desperately sorry I am that Mother Teresa won't be here at this gathering, partly because it's always an infinite joy for me to see her, because it would have been an infinite joy for you to hear her, but also because her feelings about what I am talking about are of the strongest and the deepest, which is why she agreed to come.

Her work — and to me this has been one of the great illuminations of life — her work itself is a sort of confutation of all the calculations behind this humanistic, scientific view of the world, of life, which the media and other influences are foisting upon our Western people. She considers it worthwhile to go to infinite trouble to bring a dying man in from the street in order that perhaps only for five minutes, he may see a loving Christian face before he finally dies. A procedure, which, in scientific terms or humanistic terms is completely crazy, but which I think increases enormously the beauty and the worthwhileness of being a human being in this world.

Similarly with children. She boasts, and the boast is true, I can assure you, that their children's clinic has never under any circumstances refused, however crowded it might be, to take in a child that wants to come there. I don't know if you saw the television program that was made about her called Something Beautiful for God. But in it, there is one episode that always sticks in my mind, and that is when I was walking up the steps with her and there was a little baby that had just been brought in, so small that it seemed almost inconceivable that it could live. And I say rather fatuously to Mother Teresa, "When there are so many babies in Calcutta and in Bengal and in India, and so little to give to them, is it really worthwhile going to all this trouble to save this little midget?" And she picks up the baby in the film and she holds it. And she says to me, "Look, there's life in it." Now that picture is exactly what Humanae Vitae is about.

I could talk until Kingdom Come about it and it wouldn't give such a clear notion as just that episode does. "Look, there's life in it." And life comes from God. Life, any life, contains in itself the potentialities of all life and therefore deserves our infinite respect, our infinite love, our infinite care. All ideas that we can get rid of manifestations of life which may be inconvenient or burdensome to us, that we can eliminate from our carnal appetites the consequences of carnality in terms of new life, all these notions are of the devil. They all come from below. They are all from the worst that is in us.

Just think of a Mother Teresa holding up the tiny baby with that triumphant word. "Look! There's life in her." And that's what we Christians have got to think about and hold on to in times when all that signifies is and will be under attack.

I don't want to close what I've been saying to you tonight, leaving the impression with you that I feel pessimistic. Of course, I can see, as anyone must, who looks at what's going on in the world, the terrible dangers. Pascal puts it very well, you know. He said that when men try to live without God — which is what, in fact, is happening in the Western world now, men and women are trying to live without God — Pascal says when they do that, there are two inevitable consequences: either they suppose that they are gods themselves and go mad, (and we have seen enough of that in our time), or they relapse into mere animality.

And of course what Pascal himself didn't see is that even to say they relapse into animality is a kind of gloss on what truly happens. It is something much worse than animality. It's not losing the sacramental idea of carnality of eating in order to have the mere animal idea, but it is moving from the sacramental notion to the really sick notion of treating something that is by its nature related to this human creativity as itself a pleasure and a pleasure that we should demand to have.

Now, I don't want you to think that in pointing that out, I'm merely indulging in pessimism because it is not so. It is not possible to love Christ and to love the Christian faith and to see what it has done for Western man in the last 2000 years without feeling full of hope and joy. Not possible. Of course, it is possible that the particular civilization that we belong to can collapse as others have. Of course it is possible that what is called Christendom can come to an end.

But Christ can't come to an end.

And when we look around, even in this somber world of today, we have to notice one enormously hopeful thing. And that is that the efforts to create this world without God, whether through the means of shaping men and controlling men and molding men into a particular sort of human being, as the Communists have sought to do, or by the mere acceptance of libertinism, of self-indulgence, as Western people have sought to do, in both cases have proved a colossal failure.

From Communist countries, we had the voice of someone like Solzhenitsyn. In his recent speech at Harvard, which was a marvelous speech, he said that out of the great suffering of the Russian people would come some new great hope and understanding that the world lacked. And that out of the very failure of our efforts in the West to escape from the reality of God by the absurdities of affluence, we might expect men to recover their sense of what is real and to escape from a world of fantasy.

You know, it is a funny thing. When you are old, there is something that happens that I find very delightful. You often wake up about half past two or three in the morning when the world is very quiet and, in a way, very beautiful. And you feel half in and half out of your body. As though it really is a toss-up whether you will go back into that battered old carcass that you can actually see between the sheets, or to make off to where you can see in the sky, as it were, like the glow of a distant city, what I can only describe as Augustine's City of God.

And at that moment, in that sort of limbo between those two things you have an extraordinarily clear perception of life and everything. And what you realize with a certainty and a sharpness that I can't convey to you is first of all, how extraordinarily beautiful the world is; how wonderful is the privilege of being allowed to live in it as part of this human experience; of how beautiful the shapes and sounds and colors of the world are; of how beautiful is human love and human work and all the joys of being a man or a woman in the world.

And at the same time, with that, a certainty past any word that I could pass to you, that as a man, a creature, an infinitesimal part of God's creation, you participate in God's purposes for His creation. And that whatever may happen, whatever men may do or not do, whatever crazy project they may have and lend themselves to, those purposes of God are loving and not hating, are creative and not destructive, are universal and not particular. And in that awareness, great comfort and great joy.

That's the speech that Malcolm Muggeridge gave in San Francisco in July 1978.

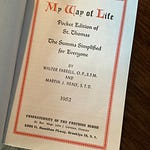

And I'll just say, as I said at the beginning, that I read it because it was one of the things that I inherited from my father's —. When my father died, I got the collection of his Catholic books and pamphlets. And I have been working my way through them for a few years. And I read this one a few months ago.

And along with the other authors that I listed at the beginning, he, Malcolm Muggeridge, could see where the policies and the programs that were coming into being in the 1960s and had also come into being in the 1940s and earlier, where those were taking society and families and individuals, and that it was not going to be good.

But they could also see that there was an arc to it. They were at the beginning of the arc, and we, I think, are closer to the end of the arc and the point at which people do realize that humans were made by God in a certain way, with certain characteristics and features, and that when we abandon those things and try to pretend that they don't exist, we get into terrible trouble.

And that when we remember those things and try to live aligned with them, then things can get better.